At work this past winter, I joined a company-wide challenge, promising to read one book a week for ten consecutive weeks. The pace seemed intimidating, but I read quickly and I managed to stay on top of it, finishing 11 books in ten weeks. My momentum carried after the challenge, though, and I established a new annual goal: read 52 books in 2024, one for each week.

I set up my Goodreads Reading Challenge and downloaded the app. I added friends and online acquaintances to my account. I marked every book I started, noted my progress, and, upon finishing a book, reached for my phone with indignant pride, eager to mark the book as “Read.” Done, all gone. No more book!

The moment I changed the status of a book to “Read,” I received an email from Goodreads with recommended titles available for purchase through Amazon, the subject line demanding, “What’s next?” And so, on to the next one.

I hurried from one book to the next, refusing myself the loving, post-book linger. I kept a running list of the books I wanted to read next, compulsively tacking on titles. I tried to stay considerate of my goal and pacing by including short reads and glib bestsellers that I knew I could fly through, but ultimately, the Notes app list was a catch-all for any interesting book. Sometimes, I’d look at the list and find my eyes scanning it manically, nonsensically, sweeping down-and-up and right-and-left, zig-zagging with panic–not really reading the text, but assessing its density. “Woof, I have a lot to read.” Upon the NYT’s summer release of the “Best Books of the 21st Century” and related readers’ choice publications, my dread grew. There was so much I wanted to read, but my time was dwindling. I had a deadline.

The anxiety about the Reading Challenge deadline reflects my general fixation on time. Time as in big “T”, Time. As in the duration of my life. The anxiety is omnipresent and sometimes overwhelming. I will die. I will die, and I will not have read all of the books I want to read, see all I want to see, love all I want to love. And since it (my demise) could happen at any time, I reason, why not entertain this fear all the time? The Goodreads Reading Challenge became a stupid stand-in for my internal doomsday clock. It’s a digital reminder of the stacks of books in my living room, on my nightstand, in the corner of my office, and of spines uncracked, pages unturned, and of my many unachieved goals and personal shortcomings.

***

When not reading, I was reminded that I ought to be reading. On TikTok, my FYP became a stream of Booktok influencers, people who post book reviews and reactions to books. They share stylish, Canva-ified slides on their Bookastagrams, showcasing the seven or ten or fourteen books they read that month. They post their incredible reading goals, screenshotting their Goodreads Reading Challenge progress bar to prove that they’re 74% done with their 150 book goal. Some Booktok/Bookstagram influencers get paid for their promotions (though not many and not much), but most are just passionate members of an encouraging—albeit zealous—online forum. Stunned that people are able to read so many books while presumably maintaining a job and social life, I felt the needling bristle of competitiveness; I had to finish this damn challenge.

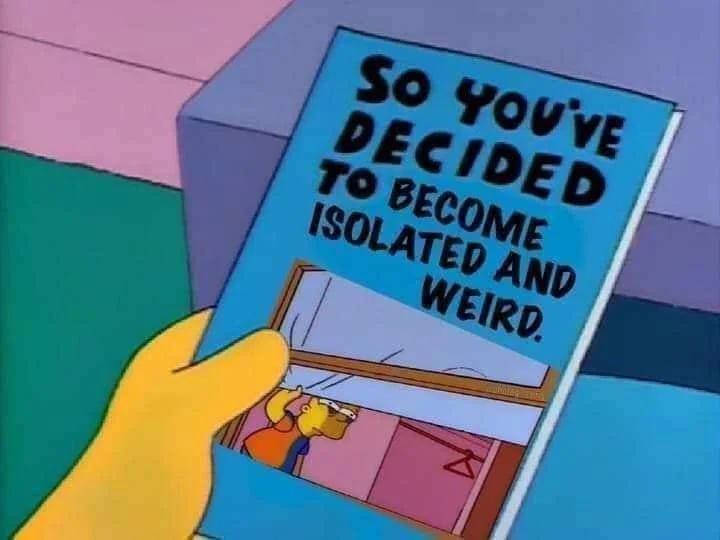

Only a month or so into the challenge, reading began to feel more like a race, each book another mile of a marathon. It took me an average of 8 days to finish a novel, and by August, I started to get selective—strategic, even—about my reading choices. I started avoiding books longer than 400 pages unless they didn’t seem to require a dictionary or Wikipedia referencing. I stayed away from books I suspected would demand my full emotional attention. Instead of reading for the sake of it, I began reading with the primary intention of finishing a book, focused on earning another point for my Goodreads tracker. I found myself Googling things like “literary graphic novels” and “best novellas list,” looking for quick scores to cushion my numbers.1

***

Culturally, we are obsessed with the quantifiable. We track everything from books read to steps walked to friends collected, and we insist these numbers mean something. Maybe industrial standards have infiltrated our lives too much; at work, we prove our worth with data points, noting growth and value metrics to explain our importance and justify our employment. But this numeric fixation has transcended our offices and resumes, and we now find ourselves demonstrating our intellectualism with the number of pages read. Cornelia Powers describes this reading behavior as: “...a quest for perfection that equates the type or number of books one reads with one’s credibility, or “purity,” as a bookworm.” And I had fallen for this quest, the performance of literacy and an aesthetic of intellectual depth; I yearned for connection through literature while hustling egotistically toward a tally.

In this quest, the messy, time-fluctuating act of reading is deflated and made linear. The goal of reading becomes less about critically experiencing a book than having finished it. The Goodreads Reading Challenge visualizes this reduction with a progress bar, scooting eastward toward a finish line with every book read.

The Reading Challenge also suggests a framework of productivity, one with measurable goals and outcomes, and a tracked schedule. By participating, one can reason that, actually, time spent reading is time spent improving one’s professional value (remember, a workplace reading challenge is what got me here in the first place). There’s plenty of literature that suggests that one’s reading “productivity” may translate to professional productivity, to capital success. Multiple times a year, yet another business magazine celebrates the reading habits of CEOs, reporting that, every day, Warren Buffet reads 500 pages, Bob Iger and Mark Cuban read for two to three hours, and, annually, Bill Gates averages 50 books and Elon Musk2 at least 100. Though Dale Carnegie and Atomic Habits will probably never leave the McKinsey summer reading list, career-minded readers are also encouraged to read fiction to “understand complex situations” and “develop emotional intelligence.” Even Harvard Business Review attests: “…the act of reading is the very activity—if done right—that can develop the qualities, traits, and characteristics of those employees that organizations hope to attract and retain.” Defying the joy of l'art pour l'art, a reader can assert that bookishness is a possible gateway toward professional success. As if, the more you read, the more likely you are to ascend executive ranks. The Reading Challenge goal is yet another quota the ambitious professional should aim to meet.

***

By flattening our engagement and objectifying reading to serve as a metric of intellectual performance or professional value, the reading experience shrinks to its material commodity: a book, read (1). The book read (1) is a data point for booksellers as well as Reading Challenge participants. And what’s better than 1? 2. Or 52 or 100 or one million. We aspire to the exponential, and, as Americans, we’re conditioned to expect it.

For Goodreads’s parent company, Amazon, reading-for-quantity culture is profitable. I’ve struggled to pin down a precise revenue figure, but we can safely assume that Amazon’s reported $150 million investment is paying off. Not only is the site a goldmine for user data, but it’s a targeted billboard, too; the beige homepage is plastered with ads for Amazon’s Audible, overwhelming the entire first fold.

Affiliate links for books Amazon publishes and sells are showcased on the Goodreads home and recommendations pages, and they get swaths of real estate in the site’s newsletters, which hit over 100 million inboxes weekly. These highly publicized books then circulate quickly and organically through Booktok and Bookstagram, where they’re promoted broadly at little cost to the publisher. Those of us on Goodreads are hungry for more!, more!, and Goodreads can literally and expeditiously deliver top-rated books via Amazon as soon as you’ve marked your latest book “Read.”

***

Throughout the year, I was keenly aware of how many books I’d read and how many I had left to read, but admittedly, this behavior wasn’t new to me. I have a personal history of numeral idiosyncrasies, of counting. As a kid, I was transfixed by the number 3. I’d try to move around with long strides, skipping or leaping from room to room in an attempt to limit my movement to 3 or an interval of 3. Making my way from my bedroom door to my bunkbed ladder in 3 strides was a defensive spell against nightmares. I felt vulnerable to bad luck, so I held my breath while passing a cemetery and for the 3 seconds before and after. I repeated the same prayer thrice before bed to protect myself and my family. As an adult, this obsession has waned, but I still tap my brake pedal 4 times before putting my car into drive, lest I die in an auto accident. I only eat odd numbers of dates. Numbers have a tendency to entrap me. Their orderliness is so appealing, if ingenuine.

***

Florida author Lauren Groff describes the challenge of writing as having to realize art through the abstract means of language, a challenge unique to writers. When composers hear music in their heads and document verbatim what they hear or a sculptor envisions an object and realizes it precisely with their medium, they know their work is finished: what they have produced matches exactly to what they had in their mind. But writers must capture the photorealistic with the clumsy, multi-symbolic mess of text. The act of writing is nonlinear, demanding exploration of time and space, of the intangible. And I think, at its best, reading is nonlinear, too, demanding the flexibility and input of imagination, interpretation, and memory. Eleanor Stern’s comparison of the reading experience to that of being alone in an empty room rings delightfully true:

“I can move around the architecture of the room in whichever direction and at whatever pace I want. I can labor over a sentence for minutes or speed through a page in seconds, I can skim, I can pause… Maybe because I live the rest of my life according to an external clock, I like the feeling of being freed from it, allowed to enter into a more internally-driven, fluid relationship to time itself.”

Since reading is abstract, disorderly work, attempting to quantify it feels ineffective, maybe even inappropriate. It’s inauthentic to capture cerebral engagement with a bar graph, so to make reading “count,” we reduce the experience to the act of having read, tallying our reads. The tally cannot reflect how closely or thoroughly or patiently we read, it does not indicate taste or knowledge, it’s a misrepresentation of the reading practice. By overvaluing the tally, we dismiss the real importance of reading by favoring consumption over engagement and experience. The tally proves only that we finished, we conquered; it’s something of a colonialistic metaphor itself.

***

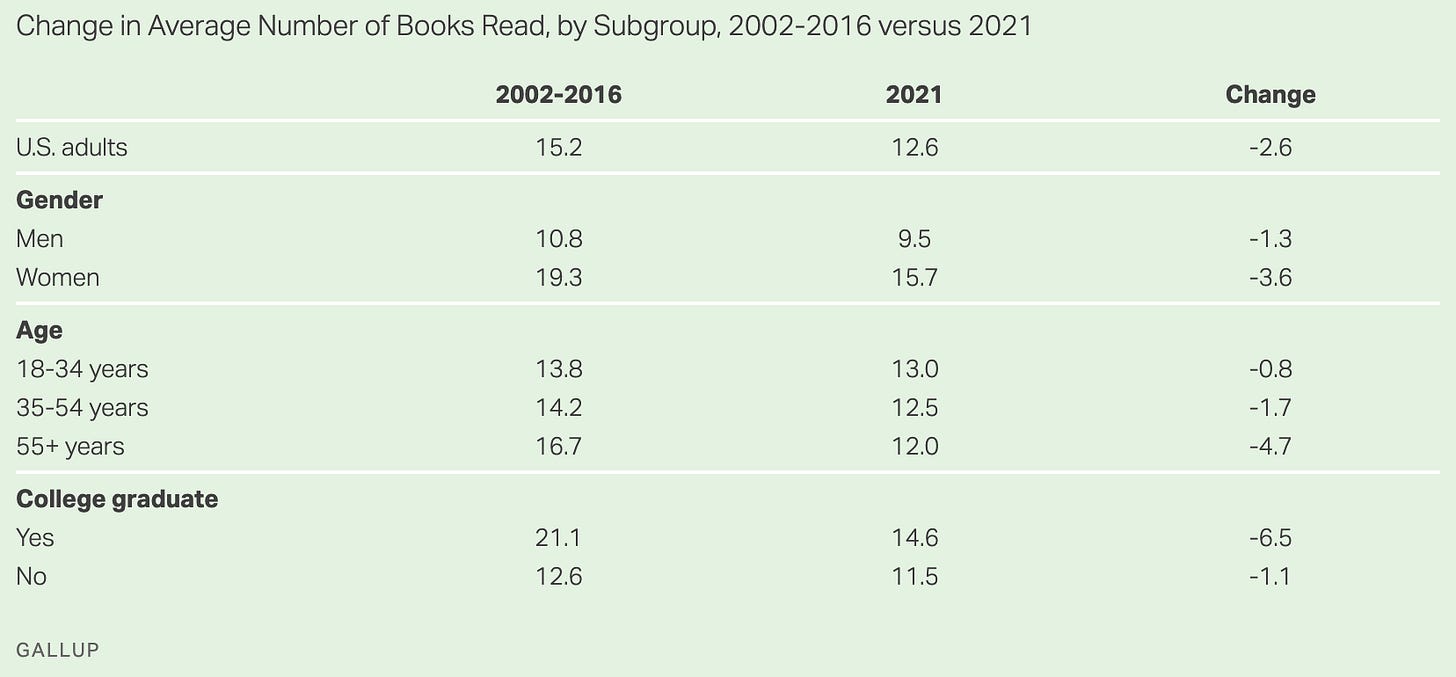

The benefits of reading challenges may go without saying; taking time to be present with a book is surely better than wasting time on social media, stealing catalytic converters, or committing arson. US literacy rates are grim, and many of us capable of reading aren’t doing it as much as we used to.

Still, I’m a bit leery of the Goodreads Reading Challenge, and I’m suspicious of sub-cultures that emphasize the quantity of books read over the quality of one’s critical engagement.

And maybe the Reading Challenge hubbub is a long-term effect of the Pizza Hut reading program. Since 1984, Pizza Hut’s BOOK IT! program has been incentivizing grade school kids to read by awarding free personal pan pizzas if they read a certain number of books over summer break. Maybe we all internalized the notion that, by reading a lot of books, we will reap some sort of reward. In the case of Goodreads, the prize is not chain restaurant pizza, but a confetti .gif and a delicious, delicious ego boost. I’d be lying if I didn’t say I felt a rush of pride when I finished my 52nd book.

Reading for quantity is an easy trap to fall into, one that encourages dimming our critical attentions in favor of consumption. And if reading serves not as exploration, enlightenment, or entertainment, but instead as a dutiful performance, perhaps we—forgive me—have lost the plot of books.

***

Though the Goodreads Reading Challenge felt downright stressful at times, I never once regretted reading. I’ve used my library much more this year. I’ve read stories by people from all over the world and throughout history, and I better understand why I read and what I like to read. As I consider what I’ll read in 2025, I don’t know that I’ll aim for a quantifiable goal. I’d simply like to read the books I delayed in 2024 because I knew they were difficult, long, and potentially a little dull. Perhaps I’ll only read “Finnegan’s Wake,” in which case, I'll see you in 28 years.

FWIW, Claire Keegan’s novellas wound up being some of the best books I read all year.

This man is so full of shit and I don’t believe anything he says.

As a very slow, nonlinear reader, I’ve avoided any and all challenges like this to prevent the inevitable shame of not hitting my goal. I often read 2 or 3 books a time, jumping between them daily. I typically finish 1 book per month, sometimes not even that. If I’m bored, I might not even finish the book at all.

But avoiding the challenges hasn’t freed me of the shame of not reading the “right quantity” of books. Every time I get notified that one of my Goodreads friends has finished a book, I take a hit of self-criticism. A realistic reading goal for me would be finishing 10-12 books a year, which is embarrassing to even admit. I hear that these “successful” CEOs read hundreds a year, and the thought rushes in before I can stop it: “well I’ll never be successful.” (Never mind that my definition of success doesn’t even remotely align with that of a CEO or those who admire them).

I absolutely love your analysis of the gamification and performance of reading driven by Goodreads and our societal obsession with numbers. After reading this, I feel more empowered to push away the shame when it creeps in. And I’ll keep savoring my books one month at a time.