Issue 04 | Fact-check, fact-check. Is this thing on?

The ethos and language of the new health expert

When I was a grad student in 2019, I took a class called “Measuring Social.” Throughout the semester, I worked on a team with four multi-disciplinary students to analyze unstructured social media data and research the social media industry broadly. Our midterm assignment required us to defend our opinion on social media fact-checking. My group was diverse, with two of us from the US and three students from across South East Asia, and most of us were pretty opinionated. When it came time to discuss the midterm project, my international teammates were unanimously and immediately against fact-checkers.

“If you believe everything you see on Facebook, you’re an idiot,” one teammate shrugged. My response was something like: “Dude, you don’t know what we’ve seen here…” For my American teammate and me, the 2016 election was very fresh, the memory of Facebook’s collapse into propaganda was still recent. And the two of us were in absolute favor of fact-checkers.

Our team discussed for a while:

Does fact-checking impede free speech? Yes, if the fact-checker automatically removes content, but not if it just notes possible misinformation.

Is fact-checking biased? Potentially yes, but less so if there’s third-party, professional oversight coupled with automated reviews.

Is fact-checking too technically expensive? No, most platforms have existing content moderation infrastructure and moderation tech is always improving.

Ultimately, it was after we collectively researched Facebook’s role in the Myanmar genocide that we all got on the same page: fact-checkers are necessary for consumer safety and national security, they help maintain the legitimacy of business accounts, and a lot of the fact-checking work can be automated (see: cheap). My support of social media fact-checker labels has since been unwavering. To me, it’s a no brainer.

So, when Mark Zuckerberg announced last week that Meta will be deprecating its third party fact-checking program, I was pissed. Meta’s fact-checking program was rolled out in response to the onslaught of 2016 US election propaganda content (some organically produced, some published by 400+ Kremlin-linked bot accounts), and expanded in 2021 to address misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine release.

Though the fact-checking labels were short and easily ignored, the pop-up misinformation warnings on Facebook and Instagram were something of a wall fortressing fact, a pause to consider the context missing from a given claim. It was, at the bare minimum, a suggestion of truth.

***

Zuck’s decision feels like another cresting wave of a cultural tide shift; American trust in institutional experts has fallen dramatically throughout the last decade, especially trust in medical experts. Since the early days of COVID, American trust in physicians and hospitals has dropped from 71% in April 2020 to just 40.1% last summer.

Such a huge change doesn’t occur in a vacuum, and I don’t believe it’s a direct reaction to any singular event. This country has a long history of medical malpractice toward vulnerable people, especially people of color, ranging from experimental C-sections on enslaved women to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study; films like The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (2017) and the popular “You’re Wrong About: Tuskegee Syphilis Study” podcast series (2020) brought some of these histories to the mainstream, and the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests motivated people to learn more about racist medical practices. COVID also made us painfully aware of how convoluted our health institutions are. The CDC’s masking and quarantining guidance was ever-changing and occasionally hypocritical through 2020-21. The back-and-forth was confusing, frustrating, and trust-eroding. Trump didn’t help.

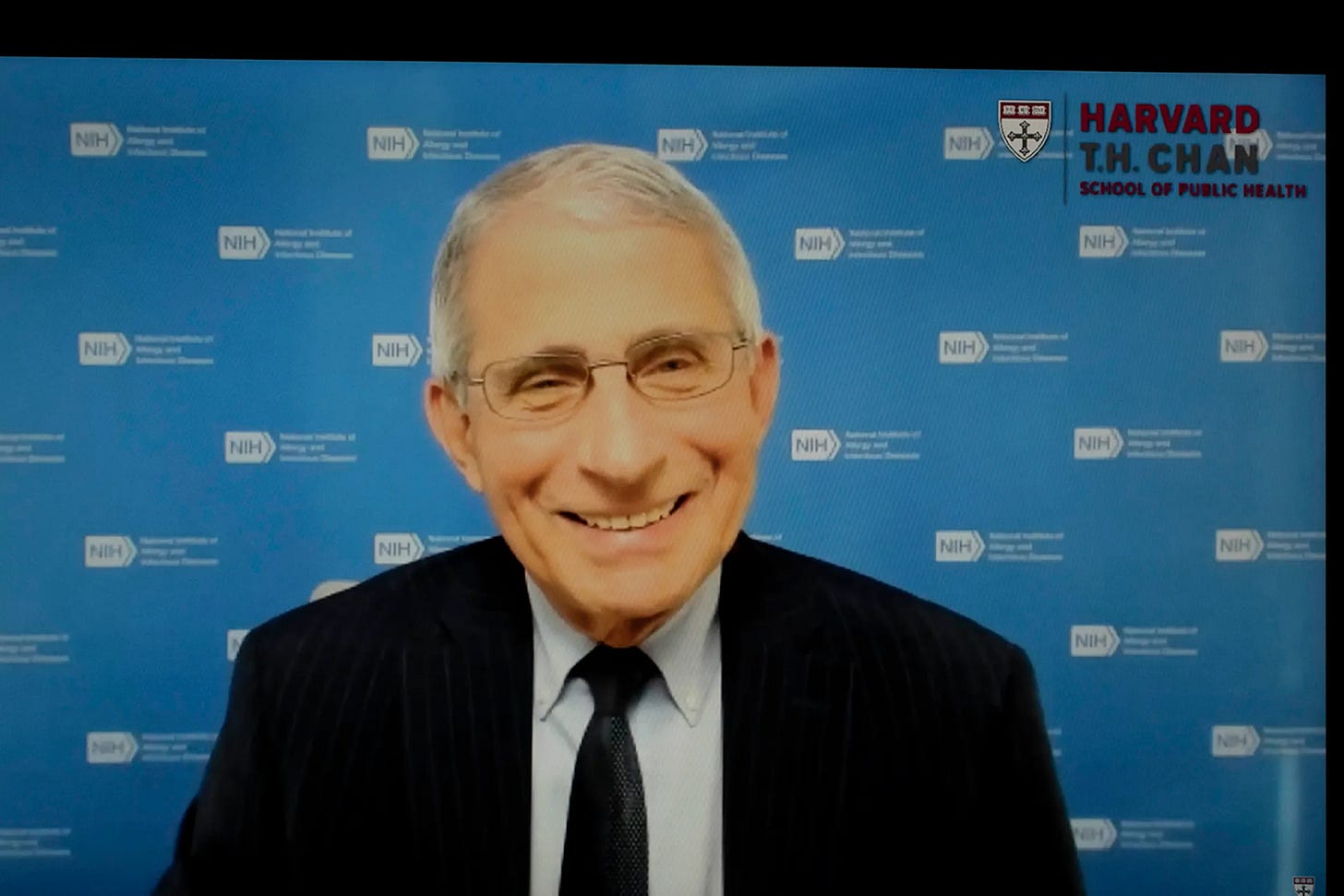

The recent, increasing distrust of the medical industry has created a chasm, inviting outsider perspectives. Skeptical of white coats, the ethos of the scientific expert is changing. Dr. Fauci, bespectacled and suited before an NIH step-and-repeat to advocate for vaccines, is a fair representative of what we could consider the “traditional” American medical expert: his age suggests experience, his dress signifies his allegiance to tradition, and the branded backgrounds often affixed behind him reflect affiliation to long-standing institutions. For some people, this presentation is comforting. But for others, Fauci symbolizes all that is outdated, elitist, and suspicious (or even conspiratorial) about our medical institutions.

As his 2021 press junkets went on, Fauci became more and more a symbol of the scientific old guard and establishment medicine. In the same year, millions of people were turning to new health and science experts.

Dr. Andrew Huberman has been one of the stand-outs of the new experts. His podcast “Huberman Lab” has amassed an audience of 5.4 million people and consistently ranks as the top “Health and fitness” podcast on Apple and Spotify since its launch in January 2021. Over 7 million people keep up with him on Instagram. With faculty status and a neuroscience doctorate from Stanford, Huberman’s a real scientist who refers to real studies, and uses real scientific terms. But unlike traditional experts like Fauci, he’s younger (and jacked). He wears Sambas and casual button-downs and keeps a neat, professorial beard, giving a cool, Californian vibe. And, unlike Fauci, he once sniffed a hit of smelling salts on Joe Rogan’s podcast. Sharing a vernacular with tech product managers, Huberman teaches listeners how to apply “protocols” to their lives so they can “optimize,” “activate,” and “biohack” their health. Huberman explains how you can leverage exercise, meditation, and nutrition to “enhance performance” and “improve productivity.”

During a time of chaos, Huberman invited Americans to take control of their lives. And though Huberman’s credentials are legit and his claims seem largely harmless (like, ok, we should eat better and work out), he’s not beyond reproach. For Slate, immunologist Dr. Andrea Love condemns Huberman’s disinterest in the flu shot and criticizes his scientific approach: “He cherry-picks weak or irrelevant studies while discarding larger and more robust studies that demonstrate something different.” By overemphasizing weaker studies and undervaluing majority-backed findings, Huberman frames scientific conclusion as debate, rather than agreed-upon fact. As a listener, it’s a more interesting framework, one that implies dissenters are as valuable to the argument as the establishment.

***

America has long celebrated the outsider and the disrupter, a phenomenon likely rooted in the country’s relationship with Christianity. Christ, after all, was a dissenter, and he stuck to his beliefs til death. The martyr is the ultimate American hero, a perspective that legitimizes going against the norm when the rebellion is an act of one’s absolute conviction. The martyr idolization is perhaps why supporters of Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) have applauded RFK Jr. for his “bravery” for “speaking out” against the medical establishment. After all, is there anyone more heroic than someone willing to defy decades of global scientific research to proselytize their deeply-held beliefs?

In “Presumption of Expertise,” rhetoric scholar Carolyn R. Miller suggests that, in the absence of logos or objective fact, a rhetor’s ethos or character can actually (with some convincing) serve as logos in their argument. The absence of fact—or the rejection of fact due to tremendous public distrust—allows self-proclaimed experts to appear as honest authorities because they don’t have establishment credentials; their amateur or unregulated expertise actually boosts their status as an expert because they’re not part of our traditional ~shadowy~ institutions.

MAHA influencers like Jessica Reed Kraus, Alex Clark, and other seed-oil-phobics have built their brands by rebelling against the scientific norm. They publish articles about “What Big Pharma Doesn’t Want You to Know” and record YouTube videos on raw milk, vaccine conspiracies, and carnivore diets. Their expertise is reflected not by establishment credentials, but by their resistance to the establishment. The women of MAHA are overwhelmingly white Christian mothers (or aspiring mothers), an identity central to their ethos.

Despite not having kids herself, Alex Clark’s “The Cultural Apothecary”1 chart-topping podcast is largely focused on moms. She shares vaccination guides for parents, discusses reversing autism in children with dye-free foods, and “debunks pro-abortion myths.” Paid for by Turning Point USA (the conservative media conglomerate, NOT to be confused with Turning Phrase, this Substack!!!), Clark uses shorthand to talk about American medical institutions, referring to establishment experts as “They” or “Them,” reinforcing an “Us vs. Them” dichotomy. They put dyes in foods so your kids get sick and you have to spend more money on medicine. They want you to vaccinate your children so that you can go to work and send them to daycare instead of staying home with your kids when they get the chickenpox. They act like they know your children better than you do, they dismiss your motherly intuition. This framework is savvy. Clark’s conspiratorial and spreads misinformation, but she also speaks to a truth: throughout the history of medicine, women’s concerns have been overlooked and misunderstood. And, though her messaging is far more political and fear-mongering than Huberman’s, she still emphasizes the opportunity for self-empowerment: “If you don’t like socialism, then you need to take control of your health.”

***

As Americans have become less trusting of our traditional healthcare systems, alternative medicine has become more attractive. The wellness industry—a massive, unregulated industry that includes everything from supplements and nutrition plans to cold plunges and Shamanic ayahuasca retreats—has exploded, growing 26% since before the pandemic and rounding out last year at an all-time high of $6.8 trillion.

It’s a good time to cash in. And it’s a really good time to be Gwyneth Paltrow, a science bro with a microphone, or a fundamentalist white woman with a million Instagram followers. During every commercial break, Huberman stresses the importance of a nutritious diet, reminding listeners that AG1 Athletic Greens are a critical part of his optimization protocol; with Huberman’s promo code, you can buy a monthly subscription of AG1 powder for $99 (though the efficacy of AG1 is contested).2 On her podcast, Alex Clark hawks every wellness product imaginable, from fitness programs to red light therapy to dehydrated beef liver. Clark and other MAHA influencers promote sponsored claims on Facebook and Instagram, offering “secret” alternatives so you can take back control of your health. Though there’s usually little (sometimes no) evidence that these wellness products work, after listening to Huberman talk with a nutrition expert for four hours about diet or scrolling through a slew of MAHA Instagram testimonies, choosing to buy powdered greens or a pack of juice shots for quick, holistic nutrients feels like a well-informed decision.

***

Our cultural mistrust of the medical industrial complex is nearly unanimous across the country, extending beyond party lines. Perhaps the most dramatic display of this attitude occurred last month, after the assassination of the UnitedHealth Group CEO. Alleged murderer Luigi Mangione’s rise to folk hero status reveals that nobody—like, truly nobody, no matter their age, social or economic status, educational background, or political affiliation—trusts how our health is handled. This moment was the most united I’d ever seen our country.

Plus, scientific literacy in the US is low: a Michigan State study found that 70% of participants could not understand the conclusions in the NYT science section. In 2019, Pew found that only half of surveyed Americans understood the scientific method. Many people don’t realize that scientific conclusions are often challenged, reevaluated, and revised, so when guidance changes, people feel as though they’ve been lied to. As MAHA influencers know, this mistrust is easy to exploit.

By removing fact-checkers, Meta is making it easier for grifters to get their bag. They’re also making the already unnavigable field of medical communication even harder to traverse.

What’s most annoying about deprecating fact-checkers is that fact-checkers are actually quite popular. Despite the conservative fury toward Meta’s Facebook and Instagram fact-checkers, the labels were effective. In 2023, MIT researchers Cameron Martel and David Rand ran 21 experiments with 14,000 participants to understand the impact of fact-checking labels. The report concluded that, while Republican participants were more likely to criticize the concept of fact-checkers, fact-checking labels were still well-received, suggesting that distrust was likely a result of superficial identity politics than a deeply-held philosophical belief. From their report, Rand summarized:

“Misinformation warning labels worked for even the respondents in our sample who were least trusting of fact-checkers and farthest right politically — and we saw no evidence of any backfire effect.”

***

In 2019, I was hospitalized with rhabdomyolysis from going too hard at a cycling class, a humiliating and painful experience (lol!). Days before I was admitted, I was on Google and Reddit, looking for people to help me fix my mysterious malady. I was massaging my legs with tennis balls and chugging electrolyte drinks and popping iron supplements. Like any good American, I was willing to try anything to avoid the hospital. And even though western medical intervention is what saved me, I’ve continued to be wooed by alternative health solutions. I’ve spent too much money on vitamins, I’ve given $400 and my DNA to a near-bankrupt tech company to "optimize” my health, and I’ve tried a lot of trendy workouts (see: rhabdo). I fall for every “This one food prevents cancer” pop science article, and I have the Whole Foods receipts to prove it.

Nobody wants to be lied to or scammed, but healthcare in this country is so expensive and so inaccessible that it feels like a relief when you find someone empathetic to the plight. But the “secrets” the MAHA new experts share and the “solutions” podcasters shill are likely just cash-grabs. Instagram won’t warn you now if you’re seeing a false claim, so let me leave you with this public service announcement: Save yourself the $100 subscription and subsequent intestinal distress and skip the Bloom SuperFoods.

This is just a footnote to say that I listened to several hours of this podcast and spent so much time on ~crunchy mama~ social media that my algorithms are totally farkakte.

Though there’s no public document disclosing the AG1/Huberman partnership details, one investigation into AG1 suggests Huberman’s making around $2 million annually from the deal.

Really well written, Lizzy. I appreciate your insight! And I laughed at myself while reading this, because I have an AG1 subscription and totally have no clue if it's helping me or not, but I am afraid to stop taking it because I have been using it for two years already lmfao

I love this piece. This is a great analysis of the health and wellness industry and the savvy way they exploit our national, valid questioning of the health industry and institutions. There are grifters everywhere and removing the fact checking banners is just going to continue allowing their misinformation run rampant.

Side note, I’m interested and terrified to see what AI models trained on this type of misinformation put out… And then when the AI generated content circulates on meta platforms, without fact checking, we’re just moving closer and closer to dead internet theory, in the worst way.